Weather Briefing

The unsettled conditions from the cold front that moved through on Saturday were still lingering in the Kalispell area. We awoke to a layer of broken clouds, but still a good amount of blue sky peeking out above. The Flight Service weather briefer said the clouds at Glacier Part International were broken at 4,500 feet and overcast at 8,500 feet. Those altitudes are reported as above ground level (AGL) so by adding the airport elevation at Glacier Park to those numbers, the MSL (above mean sea level) altitudes for the cloud layers were at 7,500 and 11,500 feet respectively.

Our plan was to fly IFR on the way back which meant a cruising altitude of at least 12,000 feet MSL. We’d be in the clouds for at least the first part of the trip, but the satellite images showed that as soon as we got to Mullan Pass (about 75 nautical miles from Kalispell) we’d be in clear skies. Spokane and Coeur d’Alene were reporting clear skies as well, so we had good VFR outs to the west if needed. The weather briefer did not have any reports of where the cloud tops were. Cloud tops reports come when pilots file in-flight reports (called PIREPs), and at 7am on this day no one had done so yet. I promised the briefer we would give him a pilot report once we got under way. I was slightly concerned about the prospect of icing in the clouds even on this hot summer day. The forecast temperature at 12,000 feet was 0° Celsius so there was a real risk of encountering icing if we weren’t above the clouds by 12,000 feet. The plan was to depart and start our climb out, and if we encountered any icing we’d just turn around and land back at Glacier Park.

We enjoyed a nice breakfast at our hotel and then headed to the airport. By the time we paid our fuel bill and got the plane ready to go at was about 9:30am. The temperature on the ground was close to 70° Fahrenheit (20° Celsius) so it felt a bit strange to be worried about icing in the clouds. The weather conditions had improved a bit. The Glacier Park ATIS reported calm winds, broken clouds at 3,800 and scattered clouds at 7,000. There was plenty of blue sky peeking out through the scattered clouds. After surveying the sky one more time before stepping into the airplane, I was glad that we were departing IFR. It would probably be possible to make this flight in VFR conditions, but I wouldn’t be comfortable doing that. Staying VFR would mean having to remain at least 500 feet below the cloud bases while still having enough altitude to clear the mountains that surrounded the airport. The term for this is “scud running” because the lower bits of clouds hanging down are referred to as scud. Some people are very comfortable doing that, but I’m not one of them.

Departure Briefing

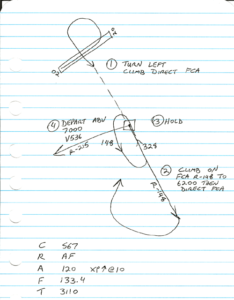

Before starting up, I reviewed the IFR departure procedure for Glacier Park with Nancy to make sure we both understood the procedure we were about to fly. Nancy doesn’t have her instrument rating yet, but she still is very helpful in backing me up when I’m flying on instruments. Talking through the procedure were about to fly is extremely helpful and calming from a VFR pilot perspective. Some IFR departure procedures are charted, but a great many of them are only supplied as a textual description. Since a picture is worth a thousand words (and I think it’s a really bad idea to try to read and interpret a bunch of fine print while flying in the clouds), I made a sketch of the departure procedure from runway 2. I’ll let you decide which one is easier to interpret.

The airplane has a Garmin GNS430 IFR GPS installed, and the database contains all the charted instrument arrivals, departures and approaches. Non-charted departures like this one are not in the GPS’s database.

We also reviewed the RNAV (GPS) 30 approach back to Glacier Park in case something went wrong shortly after takeoff and we needed to return to the airport while in the clouds. We started up the engine, got ATIS and I called up on the radio, “Glacier Park ground, Mooney 201UT with Charlie, taxi from Edwards, IFR to S67.” The ground controller replied back, “Mooney 201UT, clearance on request. Taxi to runway 2 at B6.” The full length of the 8,000 foot runway was not available due to construction, but there was still over a mile of runway for us to use.

Nancy asked what “clearance on request” meant, so I had to tell her my little story about that phrase and why it still makes me chuckle (see sidebar). Nancy agreed that it was a confusing phrase.

The ground controller called me back and advised he had my clearance for me if I was ready. I told him I’d wait until we got stopped at the B6 intersection first. I didn’t want to try to write and taxi the airplane at the same time. Our clearance was, “Mooney 201UT is cleared to the Nampa Municipal Airport, as filed, climb and maintain 12,000, expect higher altitude if requested within 10 minutes, departure frequency 133.4, squawk 3110.” You can see the shorthand I used to capture that clearance in the lower-left corner of the sketch above. The CRAFT acronym lists all the elements of an IFR clearance in the order the controller will give them to you: clearance limit, route of flight, altitude, frequency and transponder code.

We switched to the tower frequency and advised that we were ready to depart. The tower controller asked for our direction of flight, and we let him know we planned to fly the IFR departure. There was another airplane inbound on the ILS approach to runway 2, so the controller asked if we could make a climbing right turn instead of the published climbing left turn after departure. I think the controller wanted us to make that right turn to help keep us separated from the airplane that was inbound on the ILS approach. There was enough visibility beneath the clouds that I could clearly see the terrain below them. If the clouds were lower, or I was unsure whether we would have terrain clearance during the right turn, I’d wait until it was clear for me to fly the procedure as published for terrain avoidance purposes.

The sketch I made of the IFR departure procedure was quite helpful when it was time to actually fly it. Just the process of making the sketch helped me think through what I would need to do. We departed runway 2 and started our right turn towards the FCA VOR and enjoyed a good rate of climb. In fact we reached the required 7,000 feet prior to even getting to the FCA VOR so we didn’t even have to fly outbound on the 148 radial or climb in the holding pattern. We just turned right on V536 and continued the climb to 12,000. During instrument procedures, I usually stay quiet to allow Phil to concentrate. Today I felt a need to share. On the climb out I commented, “I feel safe.” With Phil in the left seat, I feel the same level of comfort whether the flight is VFR or IFR. Shortly after take off, the tower controller handed us off to Salt Lake Center who was letting us know that there was another aircraft at our 2 o’clock and 5 miles on the ILS to Glacier Park. The only thing we could see at our 2 o’clock were tall puffy clouds so we let the controller know that. In fact we were in and out of the scattered layer starting around 5,000 feet. When we hit 9,000 feet Nancy put her oxygen canula on then had me put mine on. We wanted to get that all set before we actually started flying through the solid layer of clouds that was coming up.

At around 9,500 feet we entered the overcast layer. As I saw we were getting closer to the cloud deck, I made sure the pitot heat was still on to keep ice from forming on the pitot tube (which drives the air speed indicator). I also mentally reviewed our plan if we started picking up ice: we could make a descending 180° turn to the left back down into clear air where the ice would sublimate then we could fly the RNAV (GPS) 30 approach back to Glacier Park International as we had planned before we left. Based on the scattered clouds and glimpses of blue we saw during the climbout, I expected this to be a pretty thin overcast layer and it was. I confirm all of his instrument settings and then enjoy one last glimpse of the ground before we enter the clouds. We were in solid cloud for less than a minute or two before the sunny blue sky appeared. I’m thankful for all the work Phil does to maintain his instrument rating and make this type of flight possible for us. We started to see some hints of blue at 11,000 feet and continued our climb to 12,000 in mostly clear skies. As we got over higher terrain on our way to Mullan Pass the cloud tops worked their way up, and we were in and out of the tops at 12,000 feet.

Flying in and out of cloud tops is one of my favorite things to do. No matter how fast you are going in an airplane, when you are several thousand feet above the ground it always feels kind of slow because the ground isn’t moving past you very quickly. When you are close to cloud tops you can really sense that you are moving 180 mph through the air as bits of the tops rush past you. We made the little video clip here to try to capture it, but as usual a picture is nowhere near as good as the real thing. The video doesn’t include sound, so you’ll just have to imagine Phil calling “WOOOO HOOOO!” as the cloud approaches. The perfect time for me to remind Phil of my favorite Gandhi quote. “There is more to life than increasing it’s speed.” Phil says that Gandhi didn’t get to fly a Mooney.

As we settled in to cruise flight and made our left turn at Mullan Pass towards home, I thought about how this was a perfect flight to illustrate the benefits of an instrument rating. A pilot could have legally departed Glacier Park International VFR, but on this day his options would have been quite limited. The cloud bases were just a few thousand feet above the ground near the airport and as the terrain rose to the west, the gap between clouds and mountains would close rapidly. The official term for this is “mountain obscuration” and pilots flying VFR in these conditions run serious risks of encountering the most dangerous type of cloud: cumulo-granite (that’s a mountain). Although it required a bit more planning and preparation on our part, executing the IFR departure to clear conditions on top was not very challenging and much safer than trying to make this same flight VFR given the weather conditions.

Shortly after we turned south leaving Mullan Pass, the clouds started to break up and we were greeting with crystal clear skies for the rest of the trip home. I kept my promise to the weather briefer and filed a pilot report (PIREP) on the cloud tops. I did this initially with Salt Lake Center and then I got permission to leave the center frequency to call Flight Watch to give the PIREP to Flight Service. Often routine PIREPs like cloud tops given to center controllers don’t get communicated to Flight Service (the controllers are generally too busy to do that, especially if the PIREP is not urgent). It only took a minute to switch to 122.0, and tell Flight Watch that, “Between Kalispell and Mullan Pass, skies are overcast with tops between 11,000 and 12,000 feet, clear skies and unlimited visibility above, temperature 0°, winds 320 at 17.” The person manning the Flight Watch radio was very appreciative of the PIREP (we must have been the first for that route of flight today). I try to give at least one PIREP on each flight whenever the weather is less than perfect. I know that when I’m on the ground checking weather, PIREPs tell me a lot about how the actual conditions compare to the forecast.

If you recall, we started this trip two days ago with a 15 knot tailwind. In addition to giving us nice flights in both directions, God added a extra birthday present for me by giving us tailwinds coming and going. We enjoyed the 15 knot push all the way home, got the plane put away and thanked it for carrying us on another great trip.